The Bitcoin white paper, explained in slightly simpler terms

Crypto, Blockchain, NFT, Web3 are (or were) all hot, but do you know where they all started?

This is something I had to write for my Ethereum Ecosystem class at UCD. I'm glad I took this class though, it really demystified cryptocurrency, blockchain and the related concepts around the Web3 ecosystem for me.

The staple work that started it all was definitely the Bitcoin white paper. Published on 31 October 2008 by Satoshi Nakamoto (a person or group of people, who remains anonymous even to this day), it introduced a breakthrough digital currency that is based on cryptographic principles and peer-to-peer network architecture. These are all scary words, but the way the whole system comes together is actually quite simple, though nothing short of brilliance.

To share some of what I learned, I present to you my explanation of the white paper, where I try to connect as many dots as I can so that a newcomer would understand, although a little bit of technical knowledge is still required (for terms like public key, hashing or node). This post is meant to complement the original paper, so read it accordingly.

Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System

Bitcoin is introduced by Satoshi Nakamoto in 2008 as a type of cryptographic currency. It is created out of a need for a trustless, decentralized payment system on the Internet that does not suffer from the weaknesses of a traditional, centralized one, such as the infeasibility of truly non-reversible transactions and small transactions. The technology behind Bitcoin solves most issues of digital money at the time, including the double-spending problem.

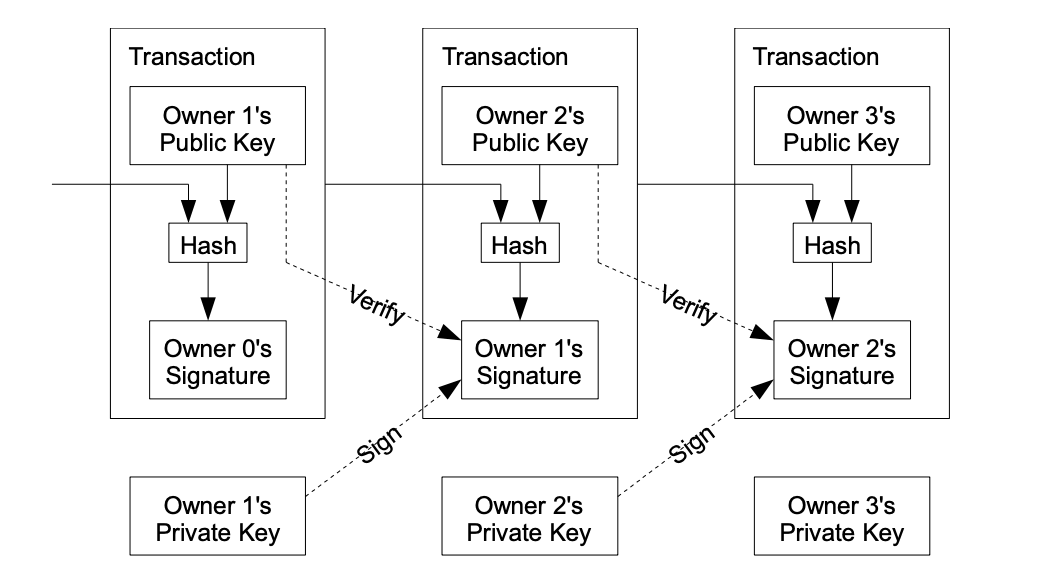

At its core, a Bitcoin is a list of signatures. Each signature is created by the previous owner of the coin (the payer) using the new owner’s (the payee) public key and the previous transaction as inputs. To prevent someone from double spending a Bitcoin, every participant (node) in the system needs to know about all transactions that have ever happened and acknowledge only the earliest one from him/her. To achieve this, a network system where all participants can agree on a single history of transactions and be notified of new ones is needed.

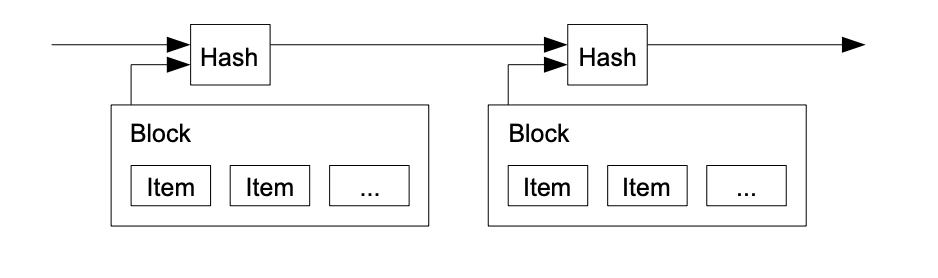

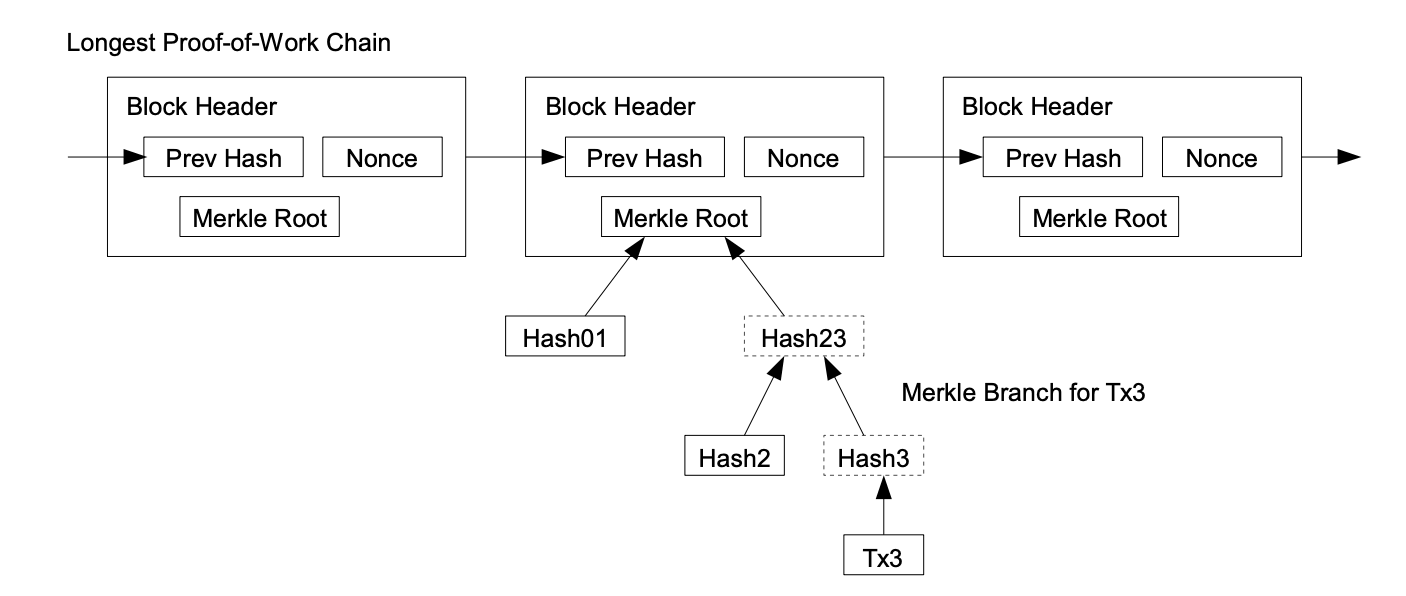

A timestamp server is one such system. It takes a block of items, hashes it, and broadcasts the hash. When nodes in the network receive this hash, they know that block exists at the time. What is special about a hash (or timestamp) is that it also contains information about its previous hash. This way, a chain is formed and if a hash is modified, subsequent hashes must also update.

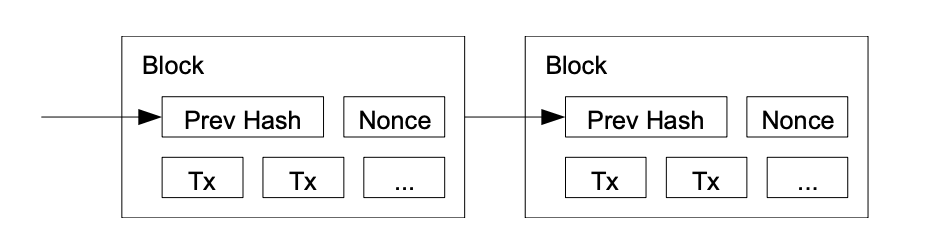

To implement the timestamp server for the Bitcoin network, which operates on a peer-to-peer basis, Nakamoto adopts a mechanism called proof-of-work. The proof-of-work mechanism requires each hash (or timestamp) created to satisfy a certain condition: it must begin with a set number of zero bits. This mechanism increases the effort needed to create a new valid block, therefore making it harder for attackers to undermine the chain, which involves redoing the work of an existing block and all the blocks after it. Proof-of-work also indicates that the determinant for the validity of the chain is CPU power, which Nakamoto calls “one CPU one vote”. As long as honest nodes in the chain have the majority of CPU power, the honest chain of blocks can outpace any attempts to attack it.

In general, events in the Bitcoin network can be described in a number of steps. First, whenever there are new transactions, they will be broadcasted to the whole network. Each node receives these transactions and groups them into a block, then starts working to find a hash that satisfies the proof-of-work condition. When a node finds a valid hash, it will notify all other nodes of the result block, which contains the “key” nonce. Other nodes will check for the validity of all transactions, and if the block is accepted it will be appended to the chain.

Edge cases can sometimes happen when two nodes find two different valid hashes and broadcast their blocks at the same time. In these cases, other nodes will keep track of both results until the next round, where the winner of the last round is determined. The consensus system also allows for a tolerance of dropped messages, so it is not a problem if new transactions or a result block do not reach all nodes.

When a node successfully hashes a block, it receives some coins as a reward. This provides both the incentive for nodes to support the network and a way to issue new coins into circulation. The number of rewarded coins halves after every 210,000 blocks, so in total there will only be 21 million Bitcoin ever generated. When there is no new coin to reward miners, they can still be incentivized by transaction fees. This incentive mechanism also acts as an added security layer, in that attackers would find it more profitable to continue mining by the rule and get rewarded instead of undermining the chain, should they ever dominate the accumulative CPU power of honest nodes.

A data structure called a Merkle Tree can be used to save storage space when a coin contains enough transactions. It also allows a non-participant of the network to verify a transaction without having to have the entire chain of blocks. In this case, it stores only the block headers, which are much more lightweight, and queries the network for Merkle Tree data. If a transaction can be traced back to a Merkle root contained in one of the headers, it is likely to be valid because the network nodes have accepted it. Subsequent blocks also further confirm its validity. However, this simplified way of verification can be compromised if attackers manage to control the chain, so businesses are recommended to run their own nodes.

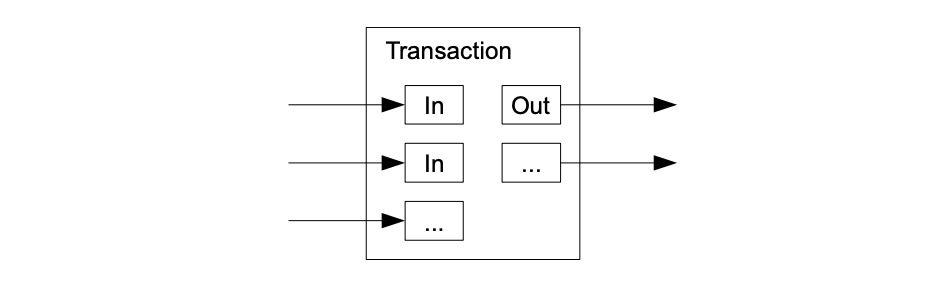

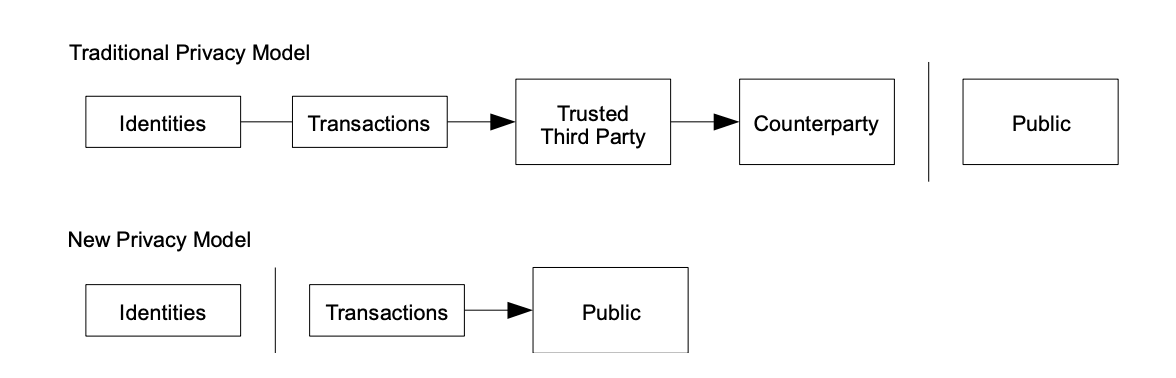

Often, transactions can contain multiple inputs and outputs, to allow combining and splitting value. A transaction is typically made up of one large input or multiple small inputs. Unlike traditional banks, Bitcoin’s publicity of all transactions requires a different approach to privacy. Each transaction is linked to a public key, but this key is kept anonymous. Unless the public key’s owner information is leaked in some way, the identities of the parties involved in a transaction remain a secret.

The peer-to-peer, consensus-based structure of Bitcoin is revolutionary and enables a truly decentralized payment system that works on the Internet. By writing code and building an anonymous system, Nakamoto realizes the Cypherpunk community’s vision for privacy that is dated from 1993 (Hughes, 1993). Bitcoin’s blockchain architecture also paves the way for many other cryptographic currencies and technologies later, with Ethereum being the leading contender that aims beyond the sole purpose of a currency.

Bibliography

- Hughes, E., 1993. A Cypherpunk's Manifesto. [Online] Available at: https://www.activism.net/cypherpunk/manifesto.html [Accessed 24 February 2023].

- Nakamoto, S., 2008. Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System. [Online] Available at: https://bitcoin.org/bitcoin.pdf [Accessed 23 February 2023].